On a sunny Saturday morning, the Bilingual Higher Pedagogical Institute of Yarinacocha, in the Ucayali region, welcomed dozens of Shipibo-Conibo shamans for an urgent meeting on the future of spiritual tourism, the defense of traditional knowledge and the protection of the forest and indigenous territories, which are increasingly under threat.

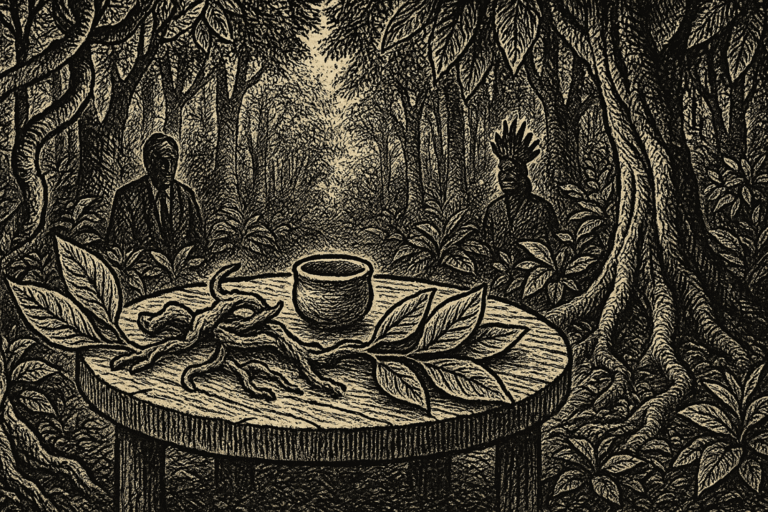

The aroma of mapacho (medicinal tobacco used in ayahuasca ceremonies) was mixed with breakfast, served on time: chicken broth with chapo, a typical Peruvian jungle drink made with bananas.

The ícaros, sacred chants sung by the onanya shaman masters, resounded through the auditorium. These chants, an essential part of ayahuasca ceremonies, have no literal translation, but its meaning is deeply rooted in Shipibo spirituality.

In Shipibo-Conibo cosmology, there is no distinction between human beings, nature and the universe: everything is connected as in an infinite network. This worldview, where diversity and reciprocity are central, was defined by the ethnographer Stefano Varese as cosmocentrism. Unlike Euro-American anthropocentrism, the expert argues, indigenous peoples have built cosmologies over millennia “based on the logic of diversity and reciprocity, in which there is no privileged center or hegemonic singularity.”

The meeting was organized by Asomashk, which stands for Asociación de Onanyabo Médicos Ancestrales (Association of Ancestral Medical Onanyabo) – the word onanyabo means ‘shamans’, in plural. Most of the debate took place in the Shipibo language – and at times in Spanish, perhaps out of consideration for this reporter, the only non-indigenous person present.

‘Through ayahuasca’

One of the main themes of the meeting was the threat of extinction of the plants used to prepare ayahuasca due to the intense trade. “People use it, but they don’t plant it,” warned shaman Walter Ramiro Lopez, president of Asomashk.

The problem is intensified by the interest of foreign pharmaceutical companies in cashing in on bringing ayahuasca to global markets. At the end of 2022, the Canadian company Filament Health announced the creation of an ayahuasca extract in capsules for clinical testing. For López, these initiatives, combined with shamanic tourism and growing global consumption, put enormous pressure on Amazonian flora. “There is a spiritual extractivism through ayahuasca. If we don’t take care of it, we’ll simply let others exploit it and take advantage.”

“In Shipibo-Conibo cosmology, there is no distinction between human beings, nature and the universe. Everything is connected.”

There is an important link between biocultural diversity and conservation. The plants used to prepare ayahuasca (the Banisteriopsis caapi vine and the leaves of the Psychotria viridis shrub) are just a few of the hundreds that local indigenous people value, use and care for. It is estimated that there are more than 400 plant species in the Ucayali region, many of which are used by indigenous communities for food and traditional medicines.

In addition, recent studies suggest that vines, such as those used in ayahuasca, are essential for forest regeneration, species diversity and ecological processes in the Amazon rainforest, especially in the tropics. Unlike other regions – such as Brazil, where ayahuasca sessions usually last a few hours – Peru is known for its deeper and longer ceremonies. Hundreds of centers in the Peruvian Amazon jungle offer retreats with the psychedelic drink, for periods ranging from 15 to 30 days, or even longer.

However, management is not always sustainable. In the Shipibo San Francisco community, a native village with many ayahuasca centers in Pucallpa, there are no collective reforestation practices. “Each master plants what he uses,” says López. Healers heard by the report agree that there is a lack of community work to conserve these plants.

‘A different kind of empirical scientist’

Asomashk was created in August 2018, about three months after the tragic death of Olivia Arévalo, the Shipibo leader murdered at the age of 81 by a Canadian tourist, who was then killed by residents of the community in retribution. Under pressure from the Canadian government to resolve the case, the community became the target of Peruvian police operations. Leaders began to be persecuted, raising suspicions that the case was being used to discourage the indigenous struggle for their rights and preservation of their territories.

Seeking solutions for the problems in the territories and the effects of the growing international interest in ayahuasca and Amazonian psychedelic tourism, the shamans decided to unite. The association currently has 152 affiliates, all masters from the Ucayali region.

“We’re giving priority to the Shipibo healers here, but our people are scattered”. According to López, many migrate to places more accessible to tourists or to work in centers run by foreigners, leaving their communities.

“Foreign ayahuasca resorts charge up to 15,000 [US] dollars for 15-day retreats”

The initiation process of a shaman involves long periods of apprenticeship, which can last for years. It involves a solitary immersion in the jungle, accompanied only by an older shaman who administers the ritualized ingestion of the so-called “master plants”, with severe dietary and sexual restrictions and very strict rules. The aim is to establish a connection between the shaman and the spirits of the plants, as well as eliminating the substances that block sensitivity, allowing him to finally find his “inner master”.

To deal with this problem, the association has started a registration process to identify how many ayahuasca centers there are and which really belong to the Shipibos. The idea is to regulate the use of traditional Shipibo medicine and the way foreign centers use the work of shamans. “There’s a lot of exploitation,” he says. “The salary they pay a master is very low compared to the work he does.”

The report found that there are ayahuasca resorts owned by foreigners that charge up to 15,000 dollars, around 80,000 reais, for 15-day retreats.

Community surveillance

The absence of spiritual leadership also makes indigenous lands and the forest more vulnerable to invasion, crime and deforestation. According to data from Maap (Andean Amazon Monitoring Project), Ucayali is one of the regions with the highest deforestation rates in the Peruvian Amazon, ranking second in 2020. In just one of the indigenous communities in the region, Flor de Ucayali, more than 20,000 hectares have been cleared in the last decade, destroying around 15% of the forest.

In 2021, the situation worsened with the completion of the last stretches of a highway – new roads are one of the main causes of deforestation in the Amazon, as they facilitate access to previously remote and untouched áreas.

“With no help from the state, the Shipibo created an indigenous guard to protect their land”

Another growing threat comes from Mennonite settlers who trace their lineage to the Reformation in the 16th century. They are members of a traditionalist Protestant sect that adheres to strict interpretations of the Bible and often carry out industrial agricultural practices Data from the Association for Amazon Conservation reveals that five Mennonite colonies in the Ucayali region deforested 2,426 hectares between January 2022 and August 2023.

Aidesep (Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Jungle) also denounces threats from criminal organizations involved in drug trafficking, logging and illegal fishing. In addition, activities by palm oil, mining and petroleum companies are encroaching on indigenous lands and deforesting extensive areas.

According to Julio Cusurichi, head of Aidesep, the government is not taking any action, despite numerous requests for help. “Timber companies operating in the Ucayali region have even denounced leaders,” he says.

A similar case occurred in the Cajamarca region, where seven environmental defenders were accused without evidence of committing various offenses for defending their territory against contamination caused by the illegal activities of a mining company.

Faced with the absence of public safety in the region, the Shipibo people decided to create an indigenous guard to protect their lands and resources. “When there’s a problem, we go to the Pucallpa police, but we don’t get any help; they claim that they lack the budget and logistics to travel,” says indigenous activist and communicator Carlos Rojas. “So we realized the need to create our own protection.”

Rojas explains that the indigenous guard is visiting and establishing bases in each community, training and empowering the indigenous people with some resources received, such as from the Shipibo Conibo Center in the United States. The aim is for all 175 indigenous communities to have their own patrols, covering more than 8 million hectares.

According to Rojas, the indigenous guards are already present in more than 20 communities. This year, there have been two large assemblies with the participation of peoples from the upper, middle and lower Ucayali who are interested in creating their own surveillance bases. “This is the only way we can protect ourselves from threats”.

(This report was produced with the support of the Earth Journalism Network)

About Carlos Minuano: Editor of Psicodelicamente, an independent digital magazine of psychedelic journalism.